String players, listen up!

That famous oboe solo in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. We’ve all heard it, but how many of us actually understand it? I mean, it is kind of weird, right? What is that? Where did it come from? Why is it there? Is it just “Beethoven being Beethoven,” and if we don’t get it, that’s because we’re not genius level, like him!

No!

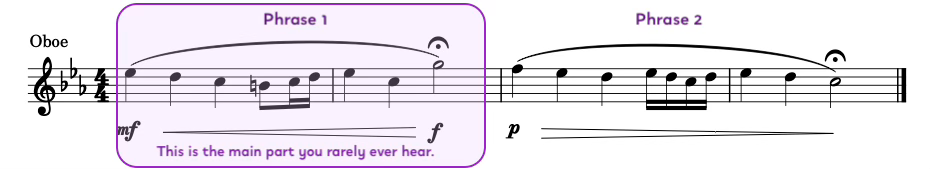

Let’s look more closely at this oboe solo. We all know it. It starts on that high G, fermata, right?

Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, 1st movement - Oboe solo

Wrong! That’s the first misunderstanding.

Let’s set the record straight: the oboe solo starts several measures before that high G fermata. And this, my friends, is the critical point that almost everyone gets wrong:

The strings don’t have the main part here, but they play as if they do. And that makes it nearly impossible to hear the actual main part, which is … the solo oboe!

This is not a mystery. Beethoven says exactly what to do. He wrote it in the score. In measure 254 he marked the first oboe part “solo” — 14 measures before the high G fermata! On top of that, Beethoven marked every instrument “piano” there, too—except for the oboe.

Why do some musicians ignore Beethoven’s instructions?

We know Beethoven wanted the first oboe to have the main part in the bars before the fermata. That’s why the oboe is marked “solo.” The strings and the other instruments are supporting the oboe, just like they would in an oboe concerto.

But why do so many orchestras ignore this?

One reason is that the strings are playing the famous main theme, and so they forge ahead and completely drown out the oboe! Sorry, string players, but you’re not the star here.

“So, what?” you may ask. “That’s their interpretation.”

Of course, musicians can do what they want. But, in this case, do they really know what they’re doing? Did they see Beethoven’s instructions and then choose to ignore them? If so, that’s an interpretation. But if they did not understand the instructions, and then choose to ignore them, that is literally ignorance.

Here’s the problem: If we don’t hear that first phrase of the solo, the second phrase simply does not make sense.

To understand this another way, let’s look at a sentence. If you hear only the second half, you might not have any idea what it means. Imagine this line is like the second half of the Beethoven solo—the only part most people ever hear:

“… and that’s why it’s cool.”

Without the first half, it doesn’t make much sense. And that first half can totally change the meaning of the whole thing:

“The sleek design of the phone has no buttons… and that’s why it’s cool.”

“That band plays with a didgeridoo in every song… and that’s why it’s cool.”

“The mountain lake is fed by glacial meltwater… and that’s why it’s cool.”

Now, let’s listen to this entire oboe solo. The first half and the second half—without the any other parts.

We hear two phrases: an antecedent-consequent structure. When we hear the first phrase, that second phrase “makes sense.” Phrase one leads to the high G; phrase two starts on the F, right after that G.

Function and Balance in Action

At the Symphonic Laboratory, we use a proven approach called MFAB—Motion, Function, Alignment, and Balance. Today, we’re focusing on the “F” for function and the “B” for balance. Understanding your part’s function and balancing it against others in the ensemble is key to making deeply moving music.

MFAB is derived from the proven methods of Leonard Bernstein, Sergiu Celibidache, and others. We make it easy to understand how the world’s top professional musicians create transcendent performances.

What should string players do?

In a great orchestra, it’s not the conductor’s job to sort this out. It’s your responsibility as a musician. The best musicians always seem to know the function or role of everything in their part, and they play it accordingly.

They don’t simply rely on a conductor to tell them what to. They check the score. They ask, “am I supporting or leading?” And then they make sure the sounds they’re making actually have that function, those relationships and roles.

Yes, oboists, the fermata G is not the first note of your solo. It’s the last note of the first phrase. Beethoven clearly indicates the start of the second phrase on F, not G.

When it’s done right, we hear the oboe’s melody, first supported by the group, and then suddenly abandoned. That’s a dramatic Beethoven moment of vulnerability and raw emotion.

Oboists, this goes for you too! Don’t play the first phrase too softly, letting the strings dominate. Be the soloist! Take a pause after the fermata to start the second phrase where it starts: on the F.

Beethoven Symphony No. 5 - The oboe solo as Beethoven wrote it

So, what else have orchestras been playing “wrong” all these years?

Are there any other spots in well-known pieces that we’ve actually been misunderstanding for centuries?

Tell us about it in the comments!

Copyright © 2024 Paul Henry Smith

Share this post